Cooperation And Punishment An Experimental Analysis Of Norm Formation And Norm Enforcement

Experimental evidence regarding contributions to public goods in heterogeneous groups is much less conclusive,5 and evidence on the enforcement of contribution norms in heterogeneous groups is basically absent.6 3The success of informal sanctioning in supporting cooperative behavior has been shown to depend on the. This includes an enhanced willingness to engage in altruistic punishment of inefficient defection. Our paper provides evidence of a dark side of group membership. In the presence of cues of competition between groups, a taste for harming the out-group emerges: punishment ceases to serve a norm enforcement function, and instead, out-group members are punished harder and regardless of whether they cooperate or defect. Key Words: Social Order, Social Exchange, Cooperation, Punishment, Strong Reciprocity. Internalization of values that induce norm compliance. Demand forces on price formation, and how they affect the distribution of the gains from. Laboratory experiments are a convenient tool for the study of social exchanges.

Social norms are an important element in explaining how humans achieve very high levels of cooperative activity. It is widely observed that, when norms can be enforced by peer punishment, groups are able to resolve social dilemmas in prosocial, cooperative ways. Here we show that punishment can also encourage participation in destructive behaviours that are harmful to group welfare, and that this phenomenon is mediated by a social norm. In a variation of a public goods game, in which the return to investment is negative for both group and individual, we find that the opportunity to punish led to higher levels of contribution, thereby harming collective payoffs. A second experiment confirmed that, independently of whether punishment is available, a majority of subjects regard the efficient behaviour of non-contribution as socially inappropriate. The results show that simply providing a punishment opportunity does not guarantee that punishment will be used for socially beneficial ends, because the social norms that influence punishment behaviour may themselves be destructive.

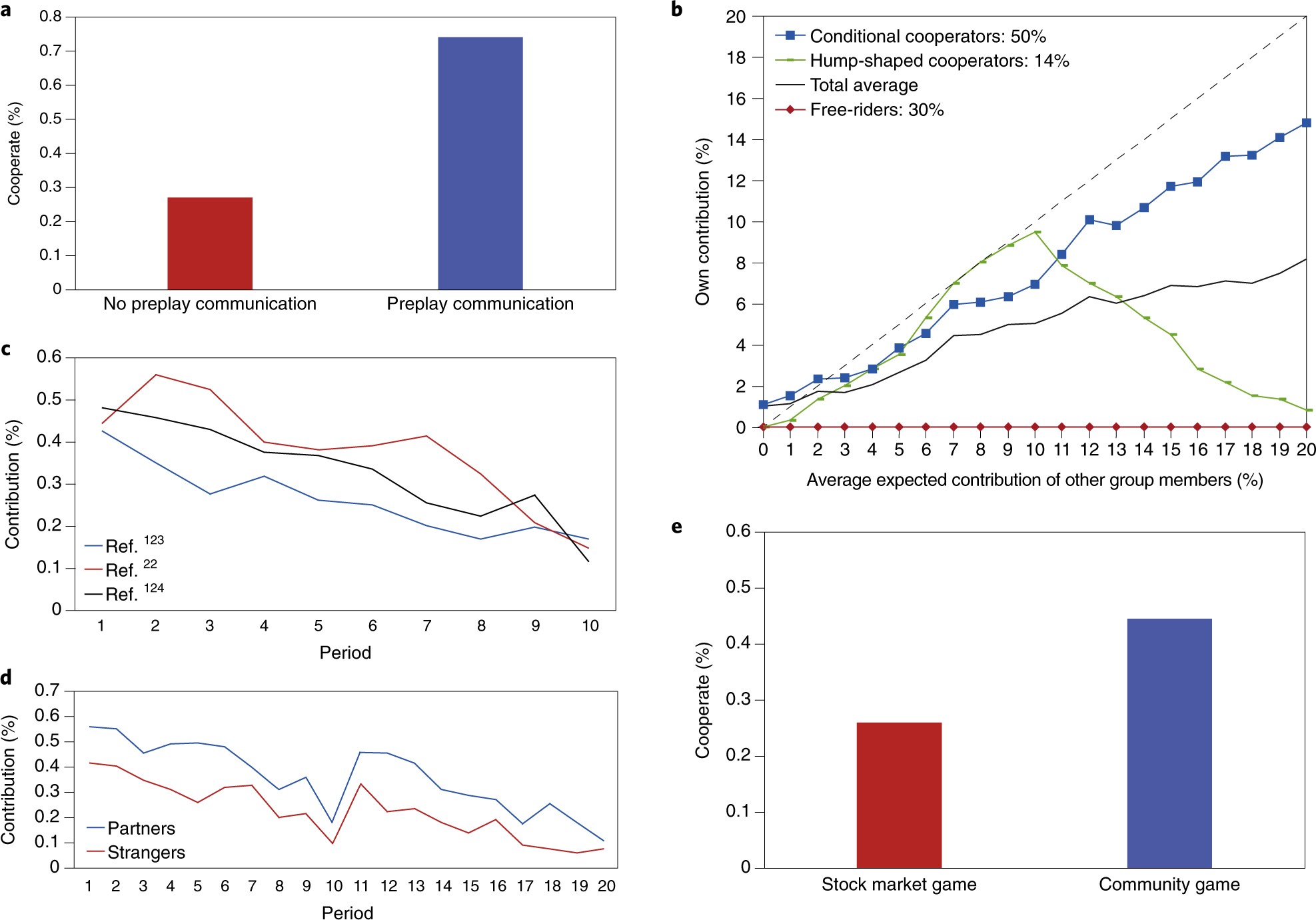

Moral, social and legal norms are crucial in sustaining the very high level of cooperation with non-relatives that is observed in human societies. Norms involve a commitment to behave in conformity with a rule, conditional on sufficiently many others sharing the commitment to that rule. They also may involve a commitment among some norm followers to punish transgressions of the norm. Punishment is likely to be especially important for the maintenance of norms that arise in social dilemmas, where there are conflicts between individual and collective interests. Economics experiments using public goods games show that providing subjects with the opportunity to inflict punishment in a social dilemma promotes higher levels of cooperation. Although the losses created by punishment sometimes outweigh the gains of cooperation, coordination of punishment and also longer periods of repeated interaction, make it very likely to be that cooperation will spread and benefit the group overall. In these cases, punishment is likely to be used to promote norms of fairness, which have prosocial effects.

Punishment is used to increase social welfare even at a personal cost to the punisher; hence, the term ‘altruistic punishment’ has been coined to describe these phenomena.Not all norms, however, are socially beneficial. For example, in some cultures, norms of sexual purity motivate punishment of transgressions, including so-called ‘honour killings’ of rape victims. Cultures of honour subscribe to norms that require violent retaliation for trivial slights, often leading to devastating escalations of violence. Even apparently benign norms of gift-giving have been identified as responsible for costly inefficiencies, amounting to billions of dollars in annual deadweight loss.This study aims to investigate whether punishment will be employed to establish socially costly norms in a paradigm that resembles earlier public goods experiments. In typical public goods games, some subjects appear to hold normative attitudes that require positive, equal contributions from all members. These attitudes are likely to combine elements of fairness (‘we should all contribute equally’) and benevolence (‘by contributing I/we make others better off’). We vary the standard public goods design, however, by setting the social benefit from contributing to be zero or negative.

Social Norms

That is, although one individual’s contributions will benefit the remainder of the group, they do not make the group better off as a whole. In this setting, normative attitudes that require positive contributions will be potentially harmful to the collective.

We hypothesise that providing subjects with the opportunity to punish in such games will allow these potentially damaging norms to influence behaviour much more than they would in the absence of punishment. Thus, groups provided with punishment opportunities will contribute more and this outcome will be mediated by the normative attitudes, held by at least some subjects, requiring positive contributions.As existing studies have used a paradigm in which cooperation was beneficial, it is unknown whether punishment can be used to elicit destructive behaviour. On the one hand, it has been suggested theoretically that if punishment is sufficiently potent, it can institute any norm, no matter how foolish. On the other hand, it is also thought that psychological propensities to adopt and enforce norms have been subject to significant evolutionary pressures, suggesting there may be significant limitations on the range of possible norms. Although some existing evidence suggests that ‘altruistic’ punishment has a dark side, our study is the first to provide experimental evidence that subjects will enforce a destructive norm with punishment.In a (linear) public good game, players are endowed with a number of monetary units (MU), which they can either keep or invest.

Invested monies are multiplied by a factor called the marginal per-capita return (MPCR) and every player in the group receives the multiplied amount. If the MPCR is between 1/ n and 1, with n being the number of players, there is a social dilemma, where the individual dominant strategy is to keep all one’s endowment, while social welfare is maximised if everybody invests all. This is the environment where punishment has proven to be effective to enforce cooperation in previous experiments.In this study we remove the social dilemma aspect from the game. In two treatments (P25 and P20) we set the MPCR to 0.25 and 0.2, respectively, where n = 4. In the former, there is no welfare gain from investments; in the latter, investments actually lower the group payoff: every dollar contributed leads to a payoff of $0.80, divided equally between the four members.

In two baseline treatments (N25 and N20), subjects play the same games, but without a punishment opportunity.We find that punishment significantly increases contributions, in both the neutral and the destructive environments. A second experiment demonstrates that subjects have shared attitudes that it is appropriate to contribute more than five units and inappropriate to contribute zero. This finding suggests that punishment in the first experiment is being used to enforce a social norm, even though in the present environment the effect of that norm is harmful, or at best neutral, with respect to group payoffs. Contributions and punishmentEighty-three out of 116 subjects (72%) in punishment treatments punished at least once.

As hypothesised, contributions were higher in the punishment treatments than in the controls. In P25, the average contribution per subject, per round was 5.6 MU; in N25, without punishment, it was 1.6. In P20, the average contribution per subject, per round was 3.4; in N20, without punishment, it was 0.7. Both differences are statistically significant (one-sided, Fisher’s two-sample randomisation test, P25 vs. N25: p = 0.002, P20 vs. N20: p = 0.007).We report in Table average punishments dispensed and received by subjects who contributed more or less than the mean amount contributed on a given round by their three co-players. Consistent with earlier findings, most punishment is dispensed by high contributors and most punishment is received by low contributors,.

A regression model, described in Supplementary Table, supports this result. In Fig., we report time series of contributions for each of the four treatments. Contributions start out high, but in the non-punishment treatments they decay significantly.

Display brightness', 'Dimmed display brightness' and'Enable adaptive brightness'.5. Now locate and click each of the following.' Asus rog brightness not working.

Similar to other public goods experiments, we find that punishment stabilises contributions at a significantly higher level,. We also observe, consistent with earlier findings, that higher rates of return lead to higher contributions (Fisher’s two-sample randomisation test, one-tailed p = 0.066 across the treatments without punishment, p = 0.071 across the treatments with punishment). Attempts to determine whether the mere threat of punishment was sufficient to maintain high contributions were inconclusive (Supplementary Fig. ). EarningsContributions were destructive in the MPCR = 0.2 treatments and so because contributions were higher in P20 than in N20, group earnings were lower.

Net of any expenditure on punishment, subjects in the punishment treatment earned 10.8 MU less on average over the course of the experiment. Normative attitudesOne possible explanation for punishment behaviour—that subjects engaged in retaliatory counter-punishment for having been punished in earlier rounds—was precluded by the design of our experiment. Subjects were not advised who had punished them on any given round and subject identifiers were randomly assigned every round, making it difficult to identify who was responsible for past punishment received. A post-experiment survey asked subjects to explain why they penalised other players (first person punishment) and to indicate why they believed others may have penalised them (second person punishment). In both punishment treatments, there was negligible evidence of retaliatory motives and the reasons most commonly cited were reasons relating to fairness and increasing contributions, as opposed to personal benefit or spite, consistent with our hypothesis that normative motivations were a significant factor (see Fig., also Supplementary Table and Supplementary Fig. ). Relative frequency of reasons cited to explain punishment.

First person reasons are responses to: ‘What was the main reason that you deducted points from the other members in your group?’ Second person reasons are responses to: ‘What do you think is the main reason that others may have deducted points from you?’ Solid arrows point to reasons cited significantly more frequently than the alternative, at the group level (two-tailed binomial test; red arrows p. The evidence from our post-experimental survey, however, is open to alternative interpretations about normative motivations. Punishment may have given rise to higher levels of contributions if some subjects used the threat of penalties to extort contributions from other group members. This behaviour would still be consistent with an attempt to ‘increase contributions’, but would not be a normative motivation, because it makes no reference to the beliefs of others as to what is socially or morally appropriate.

One might further doubt the veracity of any explanations offered after the experiment, given that they may reflect self-serving biases.Consequently, to determine whether the subjects in our original experiment shared a relevant norm, we conducted a second experiment, in which subjects were shown the instructions from either the P20 or N20 treatments of the first experiment and then asked to identify the appropriateness of each possible contribution level. We restricted our second experiment to an investigation of the MPCR = 0.2 environment, because this is the setting in which the existence of a norm requiring positive contributions is outright destructive and hence most perverse.Social norms can influence behaviour, even among those who reject the norm, because many agents regard it as important to be seen to do the right thing by the lights of the broader community,. In eliciting beliefs about norms, it is therefore important to find out what each subject thinks the other subjects believe, rather than to elicit individual opinions about what is right. Adapting a methodology that has been successfully used to study second-order beliefs about norms in other settings, we gave subjects an incentive to accurately identify what they believed other subjects believed by offering a monetary reward for identifying the response which was given most frequently.To determine whether normative beliefs are liable to vary across the treatment settings or to change through the course of play, we employed four treatments in a two-by-two design.

In the ‘zero-base’ treatments, P20z and N20z, subjects read the instructions from the original experiment and were asked to evaluate the appropriateness of each possible contribution in the very first round. In the ‘history’ treatments, P20h and N20h, subjects read the same instructions but were also shown a sequence of play that actually occurred in the first 19 rounds of the initial experiment. Subjects were then asked to evaluate the appropriateness of all possible contributions in the final round.We find compelling evidence that there was a norm requiring positive contributions. Subjects ranked the appropriateness of each possible contribution on a four-point Likert scale, which we converted to numerical scores on a linear scale from − 1 (very inappropriate) to + 1 (very appropriate). Average appropriateness scores for all contributions are displayed in Fig. There is a consistent pattern across all treatments: low contributions are regarded as inappropriate, whereas high contributions are regarded as appropriate.

Aggregating all our treatments, we observe that more than half of subjects rated contributing zero as very inappropriate. Half of subjects rated contributing one, two or three units as at least somewhat inappropriate and one quarter rated these as very inappropriate. Conversely, half of subjects rated contributions at every level greater than nine as at least somewhat appropriate and at least one quarter of subjects rated these positive contribution levels as very appropriate. The average appropriateness assessment given across all positive contribution levels is significantly higher than the appropriateness of making a zero contribution (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, z = –4.554, p.

There is further evidence that punishment is stabilising normative attitudes, derived from a closer examination of the P20h treatment. Subjects in history treatments were shown courses of interaction that actually occurred in the first 19 rounds of Experiment 1 (each of the 15 group histories was shown to precisely 2 subjects in Experiment 2), so subjects in P20h saw a variety of different amounts of punishment dispensed (mean 39, median 12, ranging from 1 to 277). Figure shows the association between the total amount of punishment observed by subjects and their normative attitude towards contributing zero. A linear regression on this data is of doubtful value, given the small number of observations, and the highly skewed distribution of punishment levels, but a non-parametric test of association such as Spearman’s rank correlation confirms that the data are almost certainly associated: subjects who observe higher punishment levels tend to have stronger judgments condemning zero contributions as inappropriate ( ρ = –0.665, p = 0.0001, n = 30).